Three intellectuals with three world views

- Nid d’Abeille

The “debate”

Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838-1897) participated in debates in the Middle East and North Africa region on the meaning of modernity and modernization. These occurred not only because of developments within the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), such as the decline of the Ottoman Empire, but also resulted from the increasing presence of European imperialism since the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon in 1798. While the Islamic world had been at the centre of the world in terms of power, science, and trade following the death of the prophet Muhammad, it was steadily but surely losing power in relation to Europe.

This gave rise to questions and debates in the MENA region around modernity, such as how to organize state and society, the role of religion and how to modernize. While these engagements with the question of modernity and counter-modernity do not make sense without the presence of Europe, we should also not ascribe it solely to Europe, as this would ignore that these debates are part of a historical process involving multiple perspectives.

Afghani’s modernity - Islamic modernism

“God does not change the condition of a people until they change their own condition”

Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (fig. 5.) has been called the Awakener of the East, as his influence as a traveling revolutionary and as one of the pioneers of the Nahda, the Islamic renaissance, continued long after his death. He inspired others with his thinking and rhetoric on colonialism, modernity, independence, the role of Islam and political activism. Afghani and his disciples Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida are seen as the central figures in Islamic modernism. It argues that Islam had to be profoundly rethought in order to face the challenges posed by the West.

Afghani’s public debate with Ernest Renan in the Journal des Débats on 18th May 1883 illustrates his thinking on modernity very well. He was responding to Renan’s lecture “L’Islamisme et la science” (Islam and science, see fig 6) given in 1883 which argued that Arabs were incapable of progress and intolerant.

“M. Renan’s talk covered two principle points. The eminent philosopher applied himself to proving that the Muslim religion was by its very essence opposed to the development of science, and that the Arab people, by their nature, do not like either metaphysical sciences or philosophy. This precious plant, M. Renan seems to say, dried up in their hands as if burnt up by the breath of the desert wind.”

According to Renan, the Muslim is thus not capable of reason but is led by religious fervor with all the attached consequences. Afghani countered that “no nation at its origin is capable of letting itself be guided by pure reason.”

Dreams of pan-Arabism

The images in figures 9 and 10 capture Nasser’s envisionment of the modernization of society very well. Nasser represents the high point of Pan-Arabism, another potential answer to modernity and how to organize state and society. This was through a revolution led from above by a socialist and secular state. The autocrat would educate the population, and this would lead to modernization and modernity. The Nasserist project was the building of a new nation based on industrialization and anti-colonial nationalism. It was, as Nasser himself described it, a social and political revolution.

“. . . we are going through two revolutions, not one . . . Every people on earth goes through two revolutions: a political revolution by which it wrests the right to govern itself from the hand of tyranny, or from the army stationed upon its soil against its will; and a social revolution, involving the conflict of classes, which settles down when justice is secured for the citizens of the united nation.”

Like Nid d’Abeille is changed significantly by its inhabitants who incorporated the balconies, on the left of fig 7, into usable living space by building walls and a roof, Nasser attempts to change the colonial map. The establishment of the United Arab Republic (1958-1961), the political union of Egypt and Syria, represents the high point of pan-Arabism and anti-colonial politics in the Arab world. As Nasser would proclaim: “Today Arab nationalism is not just a matter of slogans and shouts; it has become an actual reality.” This Pan-Arab experiment failed in 1961 following a coup by Syrian military officers dissatisfied by Nasser’s domination of Syria. The collapse of the UAR signaled the collapse of pan-Arabism and the regional popularity of Nasser.

#Islamism#

The devastating loss of the Six-Day War of 1967 and the failure of the various authoritarian regimes to deliver on their promises of modernization led to the rise of Islamism. The thinking of Sayyid Qutb is emblematic of this shift. Just as Nasser, he was part of the new educated class socialized into modernist and nationalist symbols during the colonial and direct post-colonial period. He had argued that modernity required abandoning religious traditions and moving away from the past.

“The person who is writing these lines has spent forty years of his life in reading books and in research in almost all aspects of human knowledge. He specialized in some branches of knowledge and he studied others due to personal interest. Then he turned to the fountainhead of his faith. He came to feel that whatever he had read so far was as nothing in comparison to what he found here. He does not regret spending forty years of his life in the pursuit of these sciences, because he came to know the nature of jahiliyya, its deviations, its errors and its ignorance, as well as its pomp and noise, its arrogant and boastful claims. Finally, he was convinced that a Muslim cannot combine these two sciences—the source of Divine guidance and the source of jahiliyya—for his education.”

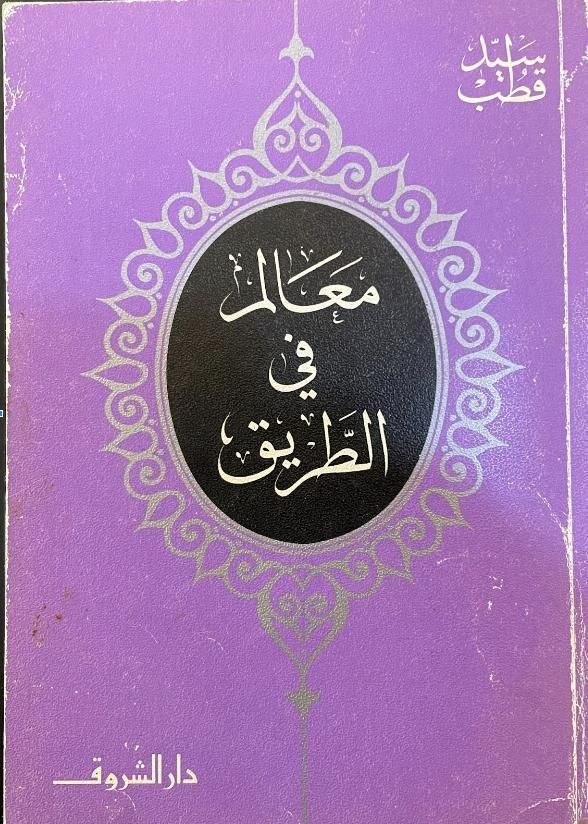

Qutb gradually shifted to actively embracing a progressive interpretation of religion as a solution to the issue of modernization and modernity. The quote you just saw comes from his book Milestones (Ma’alim fil Tariq - see fig 11) and describes his own intellectual journey as his own jahiliyya. In Milestones he dismisses all existing regimes for their embrace of nationalism and socialism, their failure to follow sharia, and their replacement of the divine with human sovereignty. He argues that not only non-Muslims, but also Muslims are jahili, ignorant. This term references the period before the rise of Islam. The usage of this language justifies confrontation with the Nasser and other regimes on religious and political grounds. These regimes were not only authoritarian but also unbelievers. The state was not an Islamic state, but a secular one which conflicted with the divine sovereignty, hakimiyya, of God. As Qutb argued:

“God (limitless is He in His glory) says that this whole issue is one of faith or unfaith, Islam or non-Islam, Divine law or human prejudice. No compromise or reconciliation can be worked out between these two sets of values. Those who judge on the basis of the law of God has revealed, enforcing all parts of it and substituting nothing else for it, are the believers. By contrast, those who do not make the law God has revealed the basis of their judgment are unbelievers, wrongdoers and transgressors.”

While Qutb did not explicitly advocate for the use of violence to overthrow these un-Islamic regimes or return people to the fold, this has been extrapolated by his followers. Qutb’s reasoning does, however, make it the duty of each individual Muslim to practice jihad to bring about the Islamic state.

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/WTAzA/views/max/640x640.jpg)

Fig 5: Al afghani - Wikimedia

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/yKdAi/views/max/540x950.jpg)

fig 6: via Bibliothèque nationale de France

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/JXkCy/views/max/414x590.jpg)

Fig 7: Muhammad Abduh - Wikimedia

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/xBSil/views/max/469x704.jpg)

Fig 8. Rashid Rida - Wikimedia

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/NUeqI/views/max/549x450.jpg)

Fig 9: Presidents Abdel Nasser and Shukri al-Quwatli Signing Unity Pact, Forming the United Arab Republic, February 1958 Wikimedia

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/dJHXo/views/max/256x315.jpg)

Fig 10: Nasser meeting with Che Guevara in 1965 Wikimedia

Fig 11: Milestones (Ma’alim fil Tariq), photo by author

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/gskfV/views/max/565x813.jpg)

Fig 12: Sayyid Qutb - Wikimedia