The Subconscious Paradox of Marine Life

- Metal Pomander

The Subconscious Paradox of Marine Life

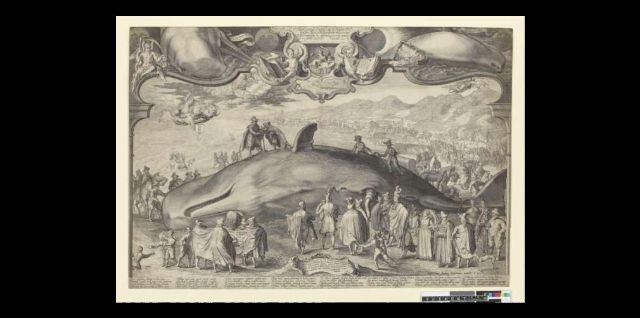

Inconsistencies and disconnections between the fascination for ambergris and the bad omen associated with whales throughout the North Sea emerged in prominent seafaring nations. The subconscious paradox that followed this obsession for whales moved beyond pure economic wealth and conveyed covert allegories and symbols that show greater symptoms of the general shift occurring in 17th century European society. This turbulence in the public sphere, through politics and religion, led to anxiety and the production of these images. Jan Saenredam’s Whale Stranded at Beverwijk on January 13, 1601 is a rich example of this, as it shows political and religious allegories while also tapping into the more scientific advances in marine biology. It engages the viewer by showing an episode that was feared by the general public, stemming from the impossibility to delimit the water regions that whales inhabited, touching on anxiety-inducing themes of invasion and statelessness.

The arctic landscapes, where most of the whales hunted by the Dutch transited, amazed navigators. This sense of awe, however, was mitigated by the harsh and unsustainable weather. Anxiety increased due to these arctic spaces being liminal, outside of the traditional, protected frontiers of the Republic. Hugo de Groot’s 1604 legal treaties cemented this as the “Delft legal prodigy […] formulated his notion of the freedom of the seas'' which deemed that sea borders were fluid, therefore providing free circulation to all.

Therefore, beached whales also symbolized political breaching, as they were considered foreign entities that washed up onto Dutch territories from alien, and thus enemy, origins.

The lack of knowledge about these particular events made way for various oracles and interpretations. The beach as a space was a physical threshold for such hostile intruders to traverse. When looking at ambergris as a material good, it is essential to look at it in relation to the host body that produces it. In this sense, ambergris was undetachable and indistinguishable from the whale which embodies the shift during the 16th and 17th centuries. This is where the paradox arises: while beached whales connotated political invasion, whaling and beached ambergris brought immense prosperity to those involved. The changing society was defined by new discoveries, not only for geographical areas as a whole but all the material goods and cultural practices that these had to offer. This new freedom of movement, scientific work, and desire for the exotic in areas outside of Western Europe blended with past but remaining superstitious and religious beliefs. Although the presence of whales on the Northern shoreline was a sign of political turmoil, these beings were also uniquely intriguing for their spectacle and aesthetic qualities, bringing people together by shared curiosity.

A Plague Upon Both Your Houses

Whale carcasses on the Dutch coast were cut up and commercialized for multipurpose decorative artifacts and oil by-products.

Figure 1: Stranded whale at Beverwijk on January 13, 1601, Jan Saenredam, 1618 (reissue of 1602 print). British Library. Engraving. H 410mm × w 593mm https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1846-0509-271

Figure 2: Hugo Grotius, by Michiel Jansz Mierevelt, 1631. Oil on canvas https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Michiel_Jansz_van_Mierevelt_-_Hugo_Grotius.jpg

Figure 3: The Battle of Scheveningen, 10 August 1653, Jan Abramhasz Beerstraten. Oil on canvas https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Battle_of_Scheveningen_(Slag_bij_Ter_Heijde)(Jan_Abrahamsz._Beerstraten).jpg

Figure 4: Detail from Stranded whale at Beverwijk on January 13, 1601, Jan Saenredam, 1618 (reissue of 1602 print). British Library. Engraving. H 410mm × w 593mm. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1846-0509-271

Figure 5: Detail from Stranded whale at Beverwijk on January 13, 1601, Jan Saenredam, 1618 (reissue of 1602 print). British Library. Engraving. H 410mm × w 593mm. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1846-0509-271

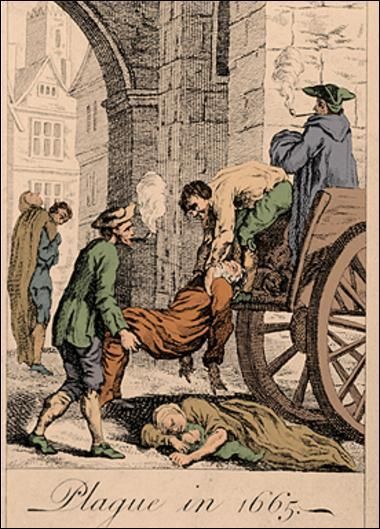

Figure 6: Collecting the dead for burial during the Great Plague. Wikipedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Plague_of_London#/media/File:Great_plague_of_london-1665.jpg

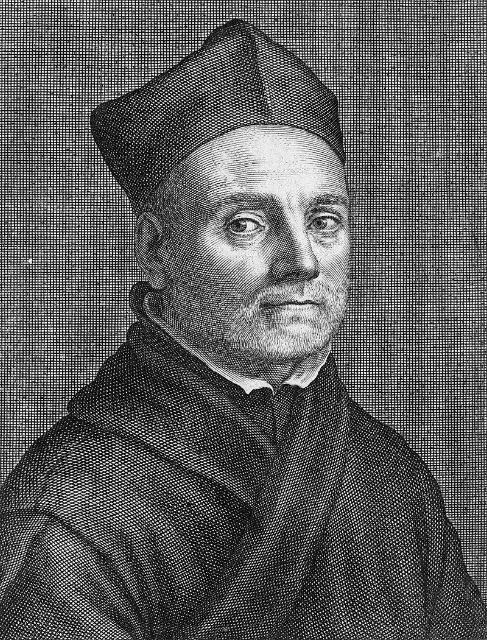

Figure 7: Portrait of Athanasius Kircher for Mundus Subterraneus. 1664. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athanasius_Kircher