The historical sensation

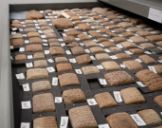

The NINO owns a collection of 3,000 clay tablets from Mesopotamia, the area of land that lies between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. They hold a treasure trove of information about life in the ancient Near East. During the Second World War, parts of the collection were kept in Germany. In order to preserve them, the Germans would bake the tablets in big ovens. Getting them back to the Netherlands would prove to be quite the challenge.

It feels almost magical, the idea that someone picked up this same exact piece of clay over 4,000 years ago, pressing signs into the soft clay with a reed stylus to record a message. There are even some clay tablets that still contain the fingerprints of the original user! History doesn’t get more tangible than that!

The decipherment of the cuneiform script, about 150 years ago, unlocked a sudden treasure trove of information about daily life millennia ago. Many texts give us a glimpse of socio-economic life, but there are also ones that contain erotic poems, school texts, laws, and literary stories, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh.

And what is perhaps the most extraordinary about these texts is that they prove how little has actually changed over all these centuries. Some things, like love, and war, are timeless.

Sebastiaan: The NINO owns the largest private collection of clay tablets in the Netherlands. In fact, the largest collection, period. A few thousand pieces.

This is Sebastiaan Berntsen again, archivist at the NINO.

Sebastiaan: They did start out as a privately owned collection, that of professor Böhl. He sold them to the institute in 1951, and they’ve been here ever since.

Indeed, the two tablets in the windowsill are part of a collection of about 3,000 clay tablets owned by the NINO. The tablets come from areas such as Anatolia, current-day Turkey, and Mesopotamia, or what is now Iraq. They tell the stories of millennia-old civilizations and bring the ruins in these parts of the world back to life.

Herman: And my father happened to be there during a time when there were a lot of digs.

This is Herman Böhl, the son of professor Böhl, the man who acquired this collection in the 20s and 30s, during his travels in the Middle East.

Herman: And he was very active on the antiquities market as well, in Alexandria, Cairo and Istanbul. He did a lot of trading there. He had a real knack for spotting what was real and what wasn’t.

Professor Böhl transported the tablets in empty cigar boxes.

Herman: Most of them were here at the NINO, but he kept tablets at home as well. As a kid, I used to crawl among the stacks of tablets stowed away under the table.

In order to preserve them, the tablets were baked after the excavation. This was done by the workers of the Chemisches Laboratorium of the Staatliche Musseen in Berlin, because they were the only ones with a suitable oven for this job.

Sebastiaan: So every now and then Böhl would ship part of his collection of tablets to Berlin to be baked. And then they would get sent back again. Except for one of the last shipments in 1939, that one never came back, because it was interrupted by the war. We have a postcard from a German colleague, who writes something like: Yeah so we’re sorry but the weather conditions are currently very bad. And also the ruins of the museum are still in such poor condition that we’re not exactly able to search for them yet. So in a way, those tablets were excavated twice, this time in the ruins of the museum in Berlin.

The fact that the Berlin museum had become a target of the bombings and was therefore heavily damaged, was obviously very unfortunate, said professor Böhl, but not exactly enough of a reason for his clay tablets not to be returned to him.

Herman: So he started corresponding with them, but he kept running into a wall. He couldn’t reach them.

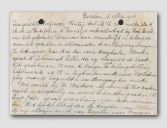

By early September 1949, Böhl’s patience had run out, so he sent a certificate of ownership to Berlin. The tablets are owned by the Dutch government and he therefore demanded immediate reclamation. In an elaborate travel log from 1950, professor Böhl describes his ‘mission’ to East-Berlin. Once he got back the cuneiform tablets, he had to come up with a way to get them across the Russian border zone. He writes:

Böhl: On July 28th I managed, with the kind help offered to me from several sides, to return the 17 packages per registered American air mail directly to a trusted address in Frankfurt. This was the safest route, though it did mean I had to take the long way home through Frankfurt/Mainz, via Hannover and Göttingen. Once in Frankfurt I was able to retrieve the packages and transport them back to Leiden by train on the night of August 6th.

The mission was a success: Böhl managed to get most of the clay tablets safely back to Leiden.