New insights

In the corner of the director’s office you see an antique wooden lectern. A piece of furniture that many important gentlemen of the institute stood behind to speak to their audience. In this track, we’ll tell you about the story of one of these gentlemen: Arie Kampman. He was the driving force behind the founding of the institute, and a phenomenal organizer. But he was also someone whose actions tended to raise questions. How ‘pure’ was this Kampman, really?

This antique, wooden lectern in the corner of my office is an heirloom belonging to the Böhl family. It was made in Vienna in the 20th century. Professor Böhl must have gifted it to the NINO, because ever since the founding of the institute the piece has been used for lectures, speeches and meetings.

On the lectern you see a picture of this lectern, one of the driving forces behind the NINO standing behind it: Arie Kampman.

Herman: Kampman was a phenomenon. A true businessman, and in the academic world, that’s a rarity.

This is Herman Böhl again, son of professor Böhl, who founded the NINO together with Arie Kampman.

Herman: My dad always made fun of Kampman a bit, and called him ‘mister big shot’ behind his back, which wasn’t very nice of him, because Kampman did unimaginable things for him. He took care of everything that was even slightly complicated, mainly the business stuff, Kampman did all of that. Kampman was incredible.

Without Kampman’s tireless effort, the NINO would never have become such a successful institute.

Sebastiaan: Kampman is the engine behind the institute, really. Kampman was a true organizer. He had correspondence with the whole world.

You’re hearing Sebastiaan Berntsen, archivist at the NINO.

Sebastiaan: And yes, people called him ‘the merchant of knowledge’. That was his nickname. I ran into that somewhere in a letter. Yes, the ‘mercator scientiae’ it says, I think. Ahead of his time, in that way, maybe. Especially nowadays, in a time where you have to take care of yourself financially as an academic, these are the kind of people you want in your corner.

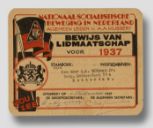

During my explorations in the archive, I ran into something that kind of shocked me. It’s an NSB membership

Sebastiaan: It seems like he had a brush with the NSB before the war, we’re talking early 1930s here. He might have been a member. We have a membership card in his name. And a register number, that’s unsigned. Yes, but I remember Prince Bernhard also telling a story like that, saying he had an unsigned NSDAP membership. So I’m not sure what that’s worth.

So how are we supposed to interpret this ‘brush’ Kampman had with the NSB?

Sebastiaan: Yes, even the NSB went through changes. In the early days, Jews were also members of the NSB. NSB was more in the corner of Mussolini’s fascism at that point. And the antisemitism and Nazism was added to that later. If you look further into NSB’s history, then you see that there’s been a power struggle within those ranks between national-socialists who, let’s say, leaned more towards the idea of a German state union of independent nation states under German rule. And then there was the more hard-lined SS wing, that really wanted to integrate the Netherlands into the German Reich. Not to put the NSB in a better light. But the story is often more nuanced than you think. For a lot of people, when they hear ‘NSB’, it’s bam! – end of discussion. And rightly so, but in the context of the time, there is greater nuance.

A time of grave economic crisis. And Kampman was a man with a thirst for action, he wanted to move forward, do things, solve problems.

Sebastiaan: Yes, a lot of people were like ‘something has to change’. It was the era of great ideologies, after all. And yeah, if you look at how things in Germany were handled, proactively, and mass unemployment was tackled. It had an impact on people. The sin of youth maybe? Let’s go with that.

Being able to radically alter your views on the way society should be organized, is business as usual in politics. Willem Otterspeer, too, came across cases like that when he was doing research for his book about Leiden University during wartime.

Otterspeer: Everyone was a nationalist in those days. You loved your homeland. That wasn’t as suspect as it is now.

Otterspeer mentions the example of the German dermatologist that came to the Netherlands at the end of the 1920s to become a professor.

Otterspeer: Then he became a member of the NSB at first, because he thought: well, those people, they love Germany, so as a good patriot, I should… and then they made it clear to him in Leiden that that was not how things were done around here, that it was a very bad decision, if he wanted to stay in Leiden at least, if he wanted to have some kind of social interaction. And then he withdrew. Eventually he turned out to be a very heated man, a romantic, who positioned himself fully behind the cause of the Small Circle. And indeed, was very, very brave and arrested a few times too, etcetera, and was in Gestel for a couple of days.

New insights and shifting values. Something that you can find enough examples of today, too. Our own ideas about displaying human and animal remains, for instance, have shifted substantially. That is done much less out in the open than it used to be.