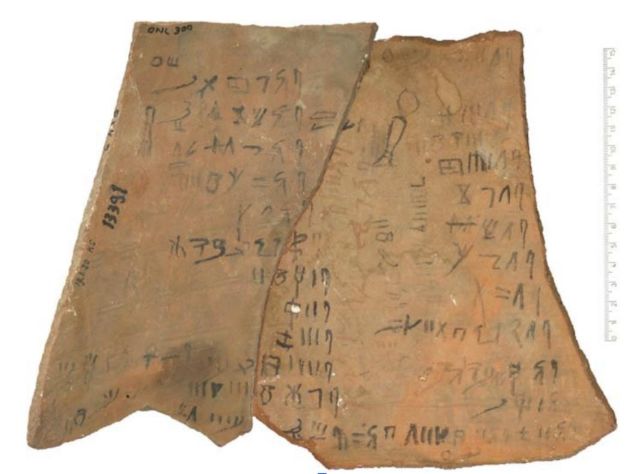

There are indications that our writer and the scribe whom we assume to be Hori worked together. They probably coordinated the administration of the deliveries to the crew as a team. It is possible that the scribe Hori often had other responsibilities at the worksite, and so our writer remained at the settlement to record the incoming commodities.See Daniel Soliman, 2018, ‘Duty rosters and delivery records composed with marks and their relation to the written administration of Deir el-Medina’, p. 162-166; 172-174; 187-190. The fact that he was not trained as a scribe was not an obstacle for him, because he used his own notation system. There are dozens of ostraca like the one in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, and research suggests that they were all made by our writer over the course of about 15 years (Fig. 1). They overlap quite well with the hieratic records produced by the scribe Hori. Assumedly, our writer handed over his ostraca to Hori, who must have been able to understand his notes. Some of the documents created by our writer contain check marks in red ink, which appear to have been made when Hori went over the documents to copy them into hieratic.

Our writer probably wasn’t a trained scribe, but he did perform some of the duties of a scribe. And his colleagues may have viewed him as a scribe. Some hieratic documents from Deir el-Medina refer to a scribe called Pentaweret, who was responsible for recording deliveries together with scribe Hori. This Pentaweret could well be the name of our writer.See Daniel Soliman, 2018, ‘Duty rosters and delivery records composed with marks and their relation to the written administration of Deir el-Medina’, p. 162-166; 189-190. We know next to nothing about Pentaweret’s personal life, but if he is indeed our writer, his documents speak volumes. During the time of our writer, several men named Pentaweret were living at Deir el-Medina, see Benedict G. Davies, 1999, Who’s who at Deir el-Medina, 109-111; 126-129, where the various Pentawerets are enumerated. The man who may have made this ostracon is Pentaweret (iii), and he may be depicted venerating a high official on the poorly preserved ostracon O. CGC 25033, see Georges Daressy, 1901, Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire, nos. 25001-25385: Ostraca, p. 8, pl. VII. They attest to his inventiveness and to a unique social environment, full of trained scribes and with a system of identity marks in place. These circumstances may have encouraged our writer to create documents like the one we have explored. Finally, his ostraca are an important reminder to us that literacy is a spectrum: between full literacy and complete illiteracy, there are many different ways in which we can engage with script.