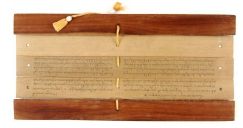

Palm leaf writing

The shape of these clay tablets, and in particular the simulated nerve in the middle of this clay ‘leaf’, suggests that real written palm leaves existed at that time and that the Mycenaeans were aware of this writing medium. Until the present day, there is a long tradition of writing on dried palm leaves in south and south-eastern regions of Asia. Although the oldest surviving palm leaf manuscript dated from the ninth century AD, the practice of palm leaf writing is much older. The absence of older written palm leaves is evidently due to the impermanence of the leaves and to the customary tradition passed on from generation to generation to copy texts on new leaves whenever a palm leaf decayed after ca. 300 years. Traditionally, the new leaves were preserved and the old leaves were burned or thrown away.

The scribes of the Linear B clay tablets were perhaps not only imitating the shape of palm leaves, but also used palm leaves for writing purposes themselves, as was the case in Asia, because palm leaves are and were abundant on Crete. This method of writing on palm leaves was probably used in the Mycenaean period, and perhaps for different communicative purposes than the administrative clay tablets. For instance, a diplomatic correspondence between the Mycenaeans and Hittites (that has largely been lost) suggests that the Mycenaean script was used more widely than we are able to ascertain now.

There is also the possibility that this palm leaf writing continued to be used in the so-called Greek Dark Ages between the destruction of the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations and the archaic Greek cities, a period during which it is assumed that the development of the Greek written language came to a standstill. This is the progressive thesis of Fredrich Ahl (1967). He argues that “there appears to have been some recollection, even in Classical times, of a tradition that the art of writing was "discovered" from writing on palm leaves.” He speculates that the term φοινικήια γράμματα ‘Phoenician letters’, that Cadmus brought to Greece in the traditional legend, has led to a confusion of terms: φοινίκινος does not only refer to ‘Phoenician’, but rather to its meaning ‘palm tree’ (φοῖνιξ). In Ahl’s interpretation, Cadmus, who was a Mycenaean king, brought not the Phoenician alphabet to Greece, but Linear B written on palm leaves that was called φοινικήια γράμματα. A writing tradition on palm leaves could solve another mystery regarding the Linear B script: the complexity of its characters seems unsuitable to be incised in clay. Possibly, Linear B was written down with a stylus on softer materials, such as palm leaves. Hence, not clay tablets, but palm leaves, for instance, were the primary writing material for the Linear B script.

In the end, the shape of this clay tablet has given us a glimpse into the lost written world of Linear B. It raises many questions: was all writing lost during the Dark Ages in that region, or have we lost only the materials they were written on? What kind of texts were written on these leaves? And how much more could we have known about the Greek Heroic Age if these leaves had survived?