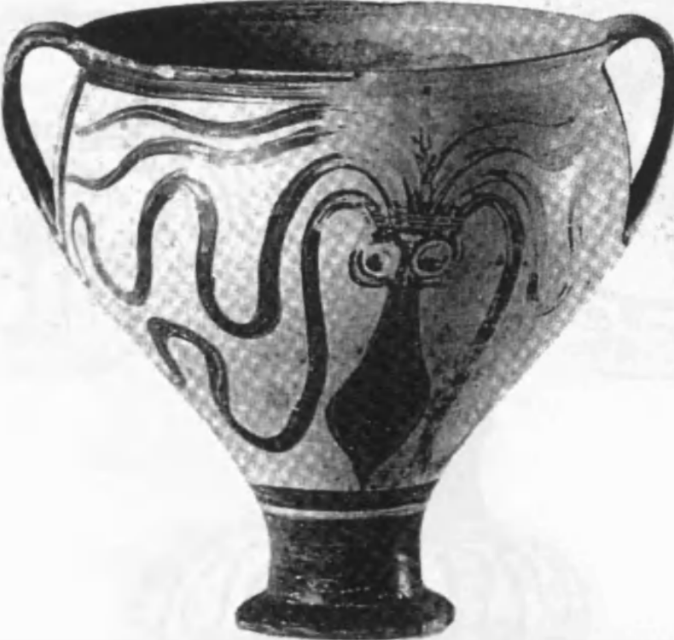

Octopus: a longer tradition?

- Mycenaean Stirrup Jar

Despite the apparent break between the Palatial and Post-palatial periods, we can also note several continuities in Mycenaean art. The existence of these continuities aligns with recent interpretations stating that the fall of the Mycenaean palaces did not form a sudden or complete collapse, but rather the outcome of a longer period of general unrest.See e.g., Rutter 1992,‘Cultural Novelties in the Post-Palatial Aegean World: Indices of Vitality or Decline?’, 70. As such, it is not surprising that the OSJs from the twelfth century - such as our stirrup jar - in some ways recall depictions of octopuses from earlier centuries.

Despite the apparent break between the Palatial and Post-palatial periods, we can also note several continuities in Mycenaean art. The existence of these continuities aligns with recent interpretations stating that the fall of the Mycenaean palaces did not form a sudden or complete collapse, but rather the outcome of a longer period of general unrest.

In fact, craftsmen from the mainland had been depicting octopods in various artistic media as early as the Pre-Palatial period (cc. 1600-1400 BCE). Like Mycenaean art from this period in general, these early productions were heavily influenced by prototypes from Neopalatial Crete. However, whereas the Cretan examples are renowned for their energetic, vivid character, the octopuses and other marine motifs from the mainland generally became static and standardized.

By approximately 1450 BCE, the iconography of the ‘Marine Style’ (which flourished between around 1500 and 1450 BCE) started to integrate with that of other styles inspired by the Minoans to form the so-called ‘Palatial Style’.

While it is difficult to prove or determine whether particular Post-Palatial artworks were (directly) inspired by some other specific piece of art, the octopus stirrup jars from both Crete and the mainland sometimes show interesting parallels with Palatial octopus art. In fact, the earliest Post-Palatial octopus stirrup jars from Crete can barely be differentiated from examples from the last phase of the Palatial period, which most likely indicates that they were produced only shortly afterwards (relatively speaking). Additionally, on the mainland some early octopus stirrup jars bring to mind octopus kraters (another type of pottery-vessel) from the final stage of the Palatial Period.

Nevertheless, there are also obvious differences. For instance, octopuses from the Palatial Period occur on a range of different media, while in the subsequent era they became virtually restricted to pottery, especially stirrup jars.

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/mMdvJ/views/max/981x640.s.png)

Figure 27: Larnax painted with an octopus and a fish, Sitia, 1440-1050 B.C.E - Archaeological Museum of Agios Nikolaos - no. 262

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/MFTuh/views/max/961x640.s.jpg)

Figure 28: Dendra Octopus Cup - Wikimedia

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/wxVDK/views/max/640x640.png)

Figure 28: “Ambushed Octopus” fragment from Knossos - Jeffrey Hurwit

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/ahLnd/views/max/1061x640.s.png)

Figure 29: Watercolor drawing by Piet de Jong of a square with octopus on the floor within the Queen’s apartments in the palace of Pylos - Carl W. Blegen

Figure 30: LH IIIA-IIIB octopus painted krater, provenance unknown - Doi 2006 - pl. 8a.