End of the queue

At the end of the 19th century, queues were cut by Qing subjects abroad as a way to blend in. Within the borders of the Qing empire, the queue had become a target of anti-Manchu actions in the early 20th century. Which of the two reasons could have been the driving force to cut off our queue? Or were there other reasons? Just as there were other reasons to cut the queue, there were also many reasons to hold on to it. We do have to realize that the voices that we hear in this story come from the more elite parts of Qing society. Many other Qing subjects, however, such as Qing laborers abroad, wanted to hold on to their queues. For instance, many of the laborers from Shandong who went to work in South Africa in 1906 kept their queues [cf]. The queue had been part of Chinese society since 1645, and getting rid of it was not an easy decision. So was our queue cut off voluntarily?

Revolutionaries like Sun Yat-sen, the provisional first president of the Republic of China, had already cut off his queue by 1895. Reformers such as Kang You-wei proposed a change of dress that resembled American and Western European style, which also meant that the queue had to go. In the first decade of the 20th century, the anti-Qing armies of Duan Qirui (1865-1936) and Yuan Shikai (1859-1916) had adopted different uniforms and cut off their queue.[cf] More and more people with influential positions wanted to get rid of the queue.

The Chinese dress was also linked to this, and often criticised in combination with the queue. Wu Tingfang (1842-1922) tried to separate the queue and the clothing, combined with attempts to depoliticize the queue [cf]. However, a final decision allowing all citizens to change their hairstyle was not yet reached.

In 1912 the empire was about to be overthrown. With the spread of the revolutionary spirit, many Chinese started to cut off their queue in order to separate themselves from the Qing government.[cf] As it became clear that the Qing dynasty was nearing its end in December 1911, the government issued an edict stating that all Chinese could wear their hair the way they wanted: having a queue was no longer obligatory for the men of China.[cf] It was abandoned on a grand scale, and Yuan Shikai, the new President of the Republic, also did his part. Diplomat Reinsch relates:

When he received me informally, he doffed the uniform of state and always wore a long Chinese coat. He had retained the distinction and refinement of Chinese manners, with a few additions from the West, such as shaking hands. His cue he had abandoned in 1912, when he decided to become President of the Republic. In the building which is now the Foreign Office and where he was then residing, Yuan asked Admiral Tsai Ting-kan Cai Tinggan whether his entry into the new era should not be outwardly expressed by shedding the traditional adornment of the head which though once a sign of bondage had become an emblem of nationality. When Admiral Tsai Cai advised strongly in favour of it, Yuan sent for a big pair of scissors, and said to him: "It is your advice. You carry it out." The Admiral, with a vigorous clip, transformed Yuan into a modern man. But inwardly Yuan Shih-kai was not much changed thereby.[cf]

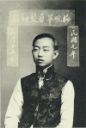

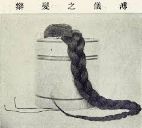

The last emperor Puyi had a similar experience. He maintained his queue even after the Qing dynasty had fallen: the Forbidden City remained occupied by the former emperor and his household until 1924. However, Puyi only cut off his queue in 1922, after conversing a lot with his English teacher Johnston. His queue is still on exhibit in the Palace Museum in Beijing.