Dragons

The exquisite material and distinct shapes of the plaque were complemented with decorative symbols and designs. At times, the plaques are decorated with symbols that might be inserted above and rarely below the cartouche. One example is actually strange to see on an abstinence plaque. It is the character for double happiness (Ch. xǐ 囍). Usually, this is a symbol associated with marriage, where each single form of 喜 represents one of the spouses. Just like the newly-weds have become bonded to one another through marriage, in the character 囍 the horizontal strokes have become interconnected. That this symbol should appear on the richly decorated abstinence plaques may demonstrate the waning devotion to imperial rituals. Instead, the court became increasingly decadent and paid more heed to appearance. As the significance of these tablets fainted, less relevant decorations were added. More common are motifs derived from the character shòu 壽 to express the wish for longevity, or a svástika, a generally auspicious sign and the first of the sixty-five footprints of the Buddha.

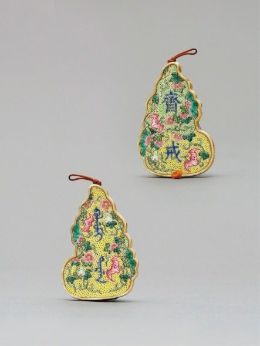

Whether or not any symbols were added, myriad decorations were always present as a frame that surrounded the cartouche. Sometimes these were comprised of flowers, tendrils, vines, and other motifs derived from nature. They hint quite obviously at the hope for fertility and growth. One such example is elaborately explained in the tour of symbols of the gourd plaque in the relevant items.

One of the most frequently used designs that border the cartouche are elaborate, curling shapes. Reminiscent of clouds, they enshroud the cartouche. At the top of the tablet, right where the cord would be fastened to suspend the tablet, the curving shapes reveal their true design. Here two noses touch, two eyes open, two maws gape: the cartouche is encircled by two dragons. They face one another; their bodies symmetrically envelop the cartouche in the centre, while their tails curl around the bottom corners to form the lower edge of the plaque.

The design of these two dragons is especially prevalent on plaques made out of various types of gemstone. These materials lend themselves especially well to the technique of carving necessary to create the gaps and emphasize the curls of the dragons’ bodies.

The dragons in Chinese art and that of surrounding regions are generally associated with benevolence; they are a symbol of good. Additionally, the dragon is the symbol for Heaven and the Emperor, especially in juxtaposition with the phoenix, which symbolizes the Earth and the Empress. There are nine different types of dragon, each with its distinct domain. The number nine is thus strongly associated with the dragon. Robert Beer writes: “Dragons have nine likenesses, nine varieties, and eighty-one dorsal scales.” Yet, the only ‘real’ dragon, the only imperial dragon is the one that has five claws. High officials and high nobility were allowed to use the four-clawed dragon, others had to put up with the three-clawed variety. The Emperor wore nine of these on and in his clothes: eight in plain sight, one hidden from view.

One type of dragon is especially relevant to the essential rain sacrifices the Emperor would perform: the Spiritual Dragon (神龍). It lived in the sky and held sway over wind and rain. Therefore, the Spiritual Dragon assumed a central role to success in agriculture. All dragons are a symbol of the “productive force of moisture, that is of spring, when by means of genial rains and storms all nature renewed itself.” It is not surprising then, that when the Emperor was observing abstinence to incur the auspicious favor of Heaven when it was most crucial in times when there was a rain shortage , that dragons would be appealed to, especially the Spiritual Dragon.

Gerelateerde objecten