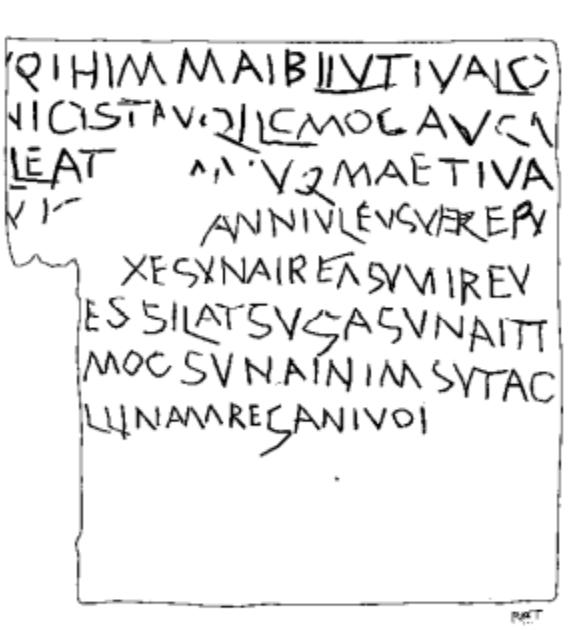

As if deciphering and translating a 2.000-year-old text is not difficult enough, this text presents an extra challenge: every word is spelled backwards. So that would make the last sentence go like this: yreve drow si delleps sdrawkcab. The order of the words in the sentence is still correct, but the words themselves are inverted. Add to that the fact that there is no spacing between the words: yrevedrowsidellepssdrawkcab. Imagine how difficult it was for translators to figure that all out! But if you know the trick, you can clearly see it on this tablet. The last word looks like ANIVOI, but actually says IOVINA (the name Jovina).

We can only guess at the function of this inverted writing. One theory is that it added to the potency of the curse through something called sympathetic magic. D. Ogden, ‘Binding Spells: Curse Tablets and Voodoo Dolls in the Greek and Roman Worlds’, in: V. Flint, et. al. (ed.), Witchcraft and Magic in Europe Vol. 2: Ancient Greece and Rome (London 1999) 1-90. The more twisted and mangled the writing on the curse tablet, the more potent it would be to inflict that same twisting and mangling on the victim. The same could be said about folding the tablets before depositing them in the water. The act of folding might have mimicked the act of binding or strangling the victim. It is essentially a kind of voodoo practice: what happens to the curse tablet, also happens to the victim of the curse.

The punishment mentioned on this tablet, ‘to become as liquid as water’, could also be an attempt at sympathetic magic. It suggests a link between the water of the spring in which this tablet was deposited, and the punishment wished upon the thief. They are to become as liquid as the water of the spring.

So after all this was done, after the ritual was complete, what happened then?