Restoration

- Minoan Larnax

The larnax is currently on display in the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam. It was acquired by the museum in November 1980 at a Sotheby’s auction in London. The shipment from England to Amsterdam was of course only the final leg of the long and dangerous journey that the larnax endured over the past three thousand years. Unfortunately, it is the only part of the larnax’ journey that we have on record, as we cannot trace back the path it travelled from Crete to London. All we know is that it must have been rough and perilous, as it hasn’t left the larnax unscathed. A report by Josefine van den Berg, a restorer at the Allard Pierson Museum, testifies to the extremely poor condition the larnax was in when it arrived at her workshop. She wrote that when she entered her studio, her desks were filled with clay bits and pieces - fragments that hardly resembled the large coffin they had once been. Once she had assembled the fragments, Josefine also discovered that the larnax in front of her had been compiled from multiple specimens, as the lid was larger than the box. So, somewhere along the way, two different larnakes were combined to form this unique historical artefact.

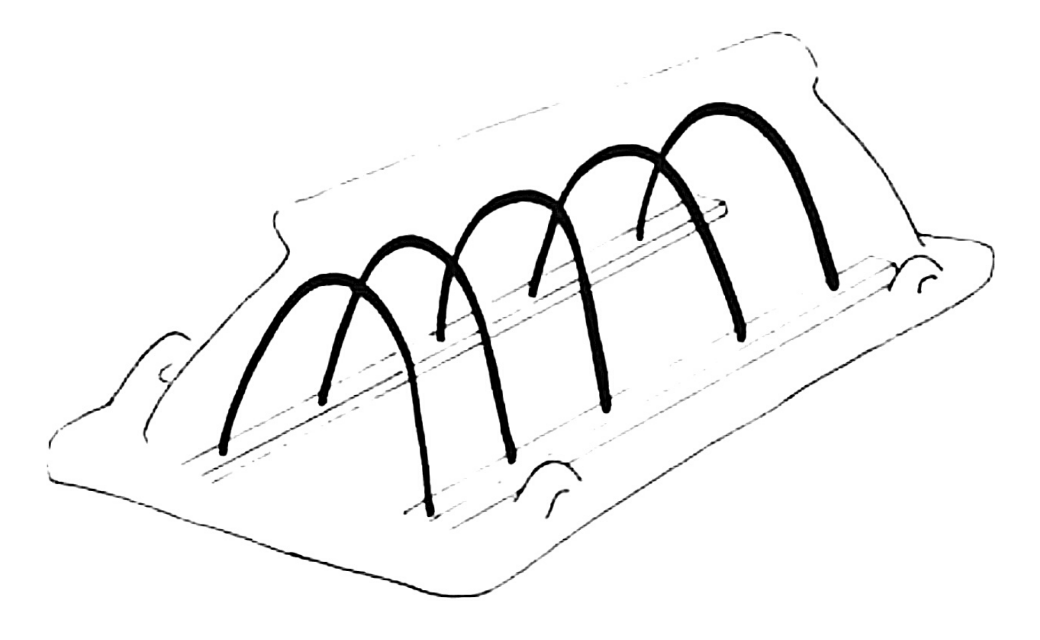

When looking at the larnax, the veins which indicate where the fragments were glued together are clearly visible, as are the missing pieces that the restorer supplemented with plaster castings. These plaster additions were painted in a lighter shade than the original clay material, so that it is clear to the visitor which parts of the object are original, and which ones were added at a later time. This is most notable in the legs of the larnax; all but one were missing when the larnax arrived in Amsterdam, and had to be remade from cement! It might be tempting to make the restorational work as inconspicuous as possible, but it is important to note the first and foremost restoration rule: any alteration made to the object should be visible and reversible. This is in line with the idea that a museum should be transparent about its objects, and that traces of restoration are part of the history of an object and should therefore not be covered up. On the other hand, a museum is also responsible for the preservation of its objects. For this reason, the inside of the larnax’ lid is full of metal pins and a wooden framework, to provide stability to an otherwise very fragile surface.