Shells on the Silk Road

As we do not know the age of the shell, it is hard to speculate when exactly it was transported from India to China. Shells, if well-preserved, can last thousands of years. We could say that from this point the story of our shell enters a dark age. Yet, it is worthwhile to look at the trade routes that existed between what are now India and China, by which our shell likely was transported.

The diving season in the Gulf of Mannar commences in October and ends in March [Cf 1836, p 188] which, not coincidentally, includes the conch’s mating season from January to March, during which they can be found in groups.[Mahadevan & Nagappan Nayar 1966, p 214-5] After conch divers return to land with their catch, the snails are taken out. The snail’s white meat is consumed by the divers. The fragrant hard lid used by the snail to seal its shell, the Operculum, is pulverized, boiled and made into incense sticks and the shell is sold.[Hornell 1914, p 29-30]

References in Tamil classics show that the conch fishery in Southern India dates back at least 1,900 years [Ibid 1914]. Up until the abolishment of the Zamindari-system in 1947, it appears that conch fishery was in the hands of local feudatory rulers. For each conch that was sold, these rulers would take their share.[Ibid, p 29-30]

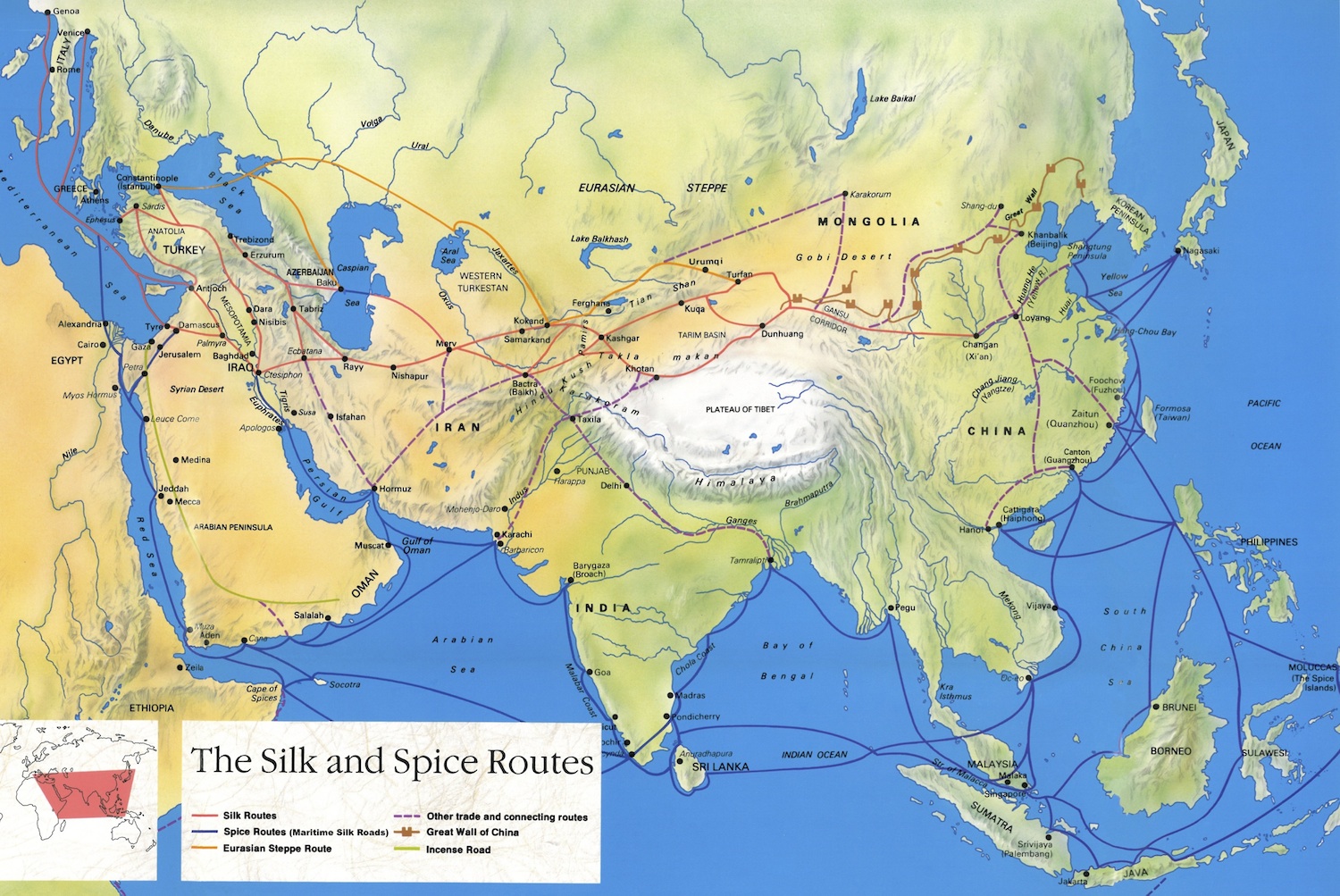

As early as the first century, a thriving maritime trade network was already established throughout Asia, stretching from Egypt to the Far East.[Abingdon 2016, p 216]. From the 7th century, this network saw a rise in the number of Arab merchants, who settled in coastal areas all over South and Southeast Asia. The coast of Southeast India, known in English as the Coromandel coast and the home of our shell, bears the name ‘Maebar’(معبر) in Arabic, meaning crossing, passage or corridor[Azam 2020]. The city of Kilakarai, which used to be a prominent trading port on the Coromandel coast, even today is predominantly inhabited by Muslims (80%), despite being situated in a province of mostly Hindus (75%).

From India these merchants would reach China by sailing through the Strait of Malacca, paying taxes on many different occasions along the way. In China, during the Song dynasty, Arabs made up the majority of merchants in trading ports. They were also present in considerable numbers throughout the Yuan and Ming dynasties [Tibbetts 1957, p 3-28]. Eventually, their numbers declined upon the arrival of European East India companies in the 17th century. But there were still great Indian ship owners whose ships easily outnumbered all European ships in the Indian Ocean at that time [Kulke & Rothermund 2016].

A vast network of land trade routes from the Near East to Far East, and vice versa, has existed for centuries. If not by boat, our conch must have made its way to Beijing by land. We know that in Tibetan Buddhist tradition Indian conches were commonly used and treasured.[Lipton et al 2013, p 4]. Conch shells do not occur naturally on the Tibetan plateau, apart from fossilized conches which are unfit to be used as trumpets. Therefore conches had to be imported. In addition, there are indications that, despite the hostile terrain, trade connections between India and China via Tibet have existed at least since the period of the Tibetan Empire in the 8th century.[Gao 2020, p 1]. Whether there is a connection with the Tibetans in Beijing who were in possession of our conch, however, is hard to prove.

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/BgPBI/views/max/191x128.jpg)