Pearl Prayer Beads

This is part of the main chain of the necklace. The entire chain consists of four times twenty-seven freshwater pearls, totalling 108 beads.

The use of freshwater pearls was reserved for the most exalted members of the imperial court in Qing regulations: the emperor himself and his closest relatives. In the case of this necklace, that relative is the emperor’s highest consort, the empress. Next to her and the emperor, only the empress-dowager and the designated crown prince were allowed to use these ‘eastern pearls’ (Ch. dongzhu 東珠). Not even the emperor’s other sons could wear them.

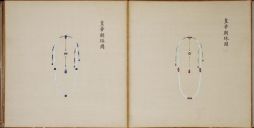

Like everything at Qing court, who could wear what was meticulously regulated. The regulations were all neatly compiled into reference works. The pages on which the Emperor’s and his wife’s necklaces are pictured are visible above.[cf]

These freshwater pearls were not easily produced. They were a treasure of great rarity and value in the Qing dynasty, not just because of their symbolic position above all other imperial ranks. The particular freshwater pearls used in the imperial necklaces were those harvested in the largest rivers of the great Manchu homeland to the north-east: the Sunggari Ula (or in Chinese songhuajiang 松花江) and the Sahaliyan Ula, the Amur, (or in Chinese heilongjiang 黑龙江). The largest round pearls found there served an even more special purpose: they were used as the ornament on top of the emperor’s hats. (See also the emperor’s hats) Nowadays, these pearls are cultivated and are not regarded as exceptionally precious gemstones.

The emperor’s other sons and all lower ranks were free to choose their preferred type of beads for the necklace, as long as the color of the string (Ch. tao 縧) in the center corresponded to that of the girdle, which was in turn assigned based on rank. Many preferred glass beads,not because of their beauty, but because of the great cost of a full string of precious stones. It is understandable , as wearing imperial necklaces was only mandated on official occasions. Even the emperor, who we know mostly from his official portraits with the necklace conspicuously present, spent most of his life without this heavy string around his neck. The Veritable Records are full of emperors stating: “regular clothing, I’m not wearing the imperial necklace!” (常服不掛朝珠)

Also, the emperor did not always wear the pearl beads. Whenever the time came for a ritual sacrifice, the emperor’s attire would depend on the type of sacrifice. The imperial necklace would be matched accordingly. A sacrifice to heaven demanded beads of lapis lazuli because of their blue color. A common Chinese saying to describe the color of lapis is that “its hue resembles the sky” (Ch. sexiang rutian 色相如天), referring to the night sky due to the shimmering specks of gold among the dark blue color, which are said to resemble stars in the night sky. A sacrifice to Earth mandated amber beads.

The fact that there are 108 small beads is the first hint to the origin of the necklace. In Buddhist tradition, it is a sacred number, the number of the Arhat [cf, p 272], and a perfect combination of threes: it is twelve times nine. Nine itself is three times three, and twelve consists of one and two, which added together make three. ‘Three’ most prominently represents the Three Jewels of Buddhism: the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Saṃgha. 108 is also the number of afflictions (Skt. śatâṣṭa-vāra), which therefore mandate that a mantra should be repeated 108 times, once for each affliction.[cf] Thus, 108 is a number filled with Buddhist meaning, and this reveals the erstwhile purpose of these necklaces. One bead per mantra is present on the string, so that completed mantras could easily be counted while concentrating fully on one’s intent during recitation.The necklace is actually in the shape of a Buddhist rosaryYet, while Buddhist prayer beads are usually not much more than a string of 108 sober beads, this necklace has a lot going on. Let’s explore some of its extra attributes.