Stap 3 van 11

Een mythe met een kern van waarheid

0:00

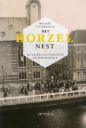

Het Horzelnest is het boek dat Willem Otterspeer schreef over de Leidse universiteit in oorlogstijd. De cover toont een foto van stakende studenten bij het gebouw van de juridische faculteit van de Leidse Universiteit. De studenten hadden zojuist een beroemd geworden toespraak van Rudolph Cleveringa bijgewoond. Cleveringa was toen de decaan van de Leidse rechtenfaculteit. Op 26 november 1940 hield hij de toespraak uit protest tegen het dreigende ontslag van de joodse medewerkers van de universiteit. Een grootschalige staking volgde en de Leidse universiteit werd tijdens de oorlog lange tijd gesloten. Het NINO bleef echter al die tijd gewoon open. Waarom werd hier een andere keuze gemaakt?

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/BRcqS/views/max/128x128.jpg)

](https://micrio.thingsthattalk.net/NExit/views/max/128x128.jpg)